When Is It Transformative and Why Does It Matter?

“Transformation: a dramatic change in form or appearance, extreme radical change.”

With the word “transformation” in open access and open scholarship, context is everything. What is transformative for a publisher may not be to the same degree for the academic research library, even when reaching for similar goals. This lack of clarity can be confusing without context. There is also a direct impact on expectations for how resources and budgets should be used to support open access and open scholarship. So, what’s in a word? Different visions of the future, or potential roles in advancing the goals of open scholarship. This article explores several examples of use and misuse of this word with the recommendation to use sparingly and appropriately and replace with more accurate terminology when available.

A Matter of Perspective

When the word “transformative” entered the scholarly publishing vocabulary, it was to encourage a switch to open access business models by publishers, especially large commercial publishers of scholarly research journals. Other players were seen as participants in their transformation. These differences of perspective seem baked into the first usages of the word by Open Access 2020 and later by cOAlition S. The focus was on eliminating or reducing behind-paywall subscriptions, especially by large publishers. This assumed library materials budgets could be repurposed to offset a transformative shift by publishers to open access.

To avoid confusion, JISC prefers to call these “transition agreements.” It is more accurate to say funders, publishers, academic institutions, research libraries are all in transition towards new types of business models and infrastructure support for research and scholarship.

Perhaps the real transformation for large publishers is from publishing companies to publishing and platform companies offering software and services directly to funders, authors, and administrators in addition to libraries. While a great topic, the focus of this review is on the impact on libraries and their budgets since cOAlition S saw this as a major source of funding for open access publishing.

Transformation in the academic setting goes well beyond agreements with publishers and repurposing library subscription budgets. There is a far bigger “transformative” view of materials acquisition, researcher outputs and open scholarship to manage.

- Collection analysis has become more complex, sophisticated, and necessary.

- Libraries are managing multiple types of business models to provide materials and resources from many types of sources.

- This rigorous assessment of current and future spending also involves funding new types of services supporting open scholarship that libraries are well positioned to provide.

Changes are a given. Transformative changes are also likely, context sensitive, and multi-faceted. The transformation of publishers to open access business models is only one small part of the transformation of the research institution to open scholarship. For academic libraries, even a flat budget does not necessarily mean static. How research institutions and libraries use their resources and budgets to meet new demands are also changing with the landscape.

“S” is for Shock

Open Access 2020 Initiative first mentioned “to transform the current subscription publishing system, an obsolete legacy of the print era, to new open access publishing models that ensure articles are open and re-usable,” stating that the focus was on changing subscription publishing business models. To further encourage open access publishing, cOAlition S secured the backing of major funders for those in compliance with cOAlition S requirements. The umbrella term, “transformative arrangements,” was adopted to include transformative agreements, transformative model agreements, and transformative journals.

Open Access 2020 and cOAlition S can be credited with jumpstarting change by shocking the publishing industry into accelerating the adoption of OA business models and fostering what we see as almost daily announcements of new licensing arrangements for journals.

In a recent example of transformative change in publishing compliant with Plan S definitions, IEEE recently announced flipping their business model. In the spirit of transparency as part of this change, they have also published the status of each of their journals and targets for compliance for all to see and review.

Another example of transparency is ACM, with cost and customer analysis used and shared as a prerequisite for moving towards a new business model of published flat fee prices for unlimited access. ACM has shared a blueprint of how to make this transition far beyond adopting a new business model. (See the presentation by Scott Delman, part of a CHORUS webinar on “Making the Future of Open Research Work,” April 23, 2021. )

Evolving Business Models: To Be Continued

The easiest way to create a new open access publishing model was to use the article processing charges (APC’s), pricing OA at the article level. In his white paper, “It’s not Transformative if Nothing Changes,” Dr. Frederick Fenter analyzes how APC’s be used to achieve the same publishing profits, market share of traditional publishers, with some discussion of the greater impact of some open access publications at lower prices.

APC’s are acknowledged for their shortcomings, with other business models to emerge like those described in the previously referenced CHORUS webinar. The APC is still behind the scenes as a potential default business model for services or as an imperfect underlying unit of measure for assumptions and calculations of cost structures, with the emphasis on the word “assumptions.”

What ARE the goals? For the large publisher, this may represent a satisfactory switch in business models that preserves and may even grow revenues. Or, the goal may simply be moving towards open access publishing with sustainable and predictable business models. For the small publisher, these changes may represent a competitive disadvantage. For the library, have they lowered subscription costs or are they now paying subscription plus open access? For the scholarly community, is there expanded support for open scholarship workflows beyond traditional publishing? In the United States, new agreements are more complex yet structured based on different goals at each institution and with each publisher.

A Tale of Two Deals

If you ask an academic librarian what they think of “transformative agreements,” it is doubtful there will be resounding enthusiasm for the word. Even if there are a growing number of agreements with new open access business modelling. For the larger research libraries, the idea of flipping models that could cost them even more is untenable. Solutions have resulted in even more agreement complexity. Sometimes these can look more like complex versions of a “Big Deal 2.0” but represent useful experimentation.

In 2021, California Digital Libraries reached an agreement with Elsevier that could be called “transformative” by cOAlition S standards, flipping the business model to primarily OA, if with refinements, covered in the Memorandum of Understanding. Excellent discussions were published in Scholarly Kitchen, Lisa Hinchcliffe’s post, The Biggest Big Deal, March 16, 2021 and Rick Anderson’s Six Questions (March 25, 2021).

The UC agreement is closer to a cOAlition S transformative agreement because the APC fees are used as a unit of calculation that does not stand alone but pays access to other content without a subscription (with extra for backfile access). With the details covered well elsewhere, we tease out one interesting thread from this landmark agreement as a multi-payer model, which is the library involvement in APC-like funding by agreeing to pay the first $1,000:

- This solves the problem of fees for APC’s exceeding materials budgets for a major research institution with significant prestige publishing while providing access to all content.

- The agreement limits support for those with grants to cover costs and covers more for those who cannot afford.

- It keeps the library as a partner / player in the eyes of the administration and faculty in the fuller scope of publisher agreements.

- Library involvement means easy collection of statistics on open access publishing and fees institution wide.

Another equally complex and interesting new type of agreement that is more traditional, not truly a transformative agreement, is the one between the Texas Library Coalition for United Action and Elsevier. Susan D’Agostino, technology and innovation reporter for “Inside Higher Ed” provides an excellent review of the deal in her article, “Is a Deal Between 44 Texas Colleges and Elsevier ‘Historic?’” (December 9, 2022). This agreement includes lowering costs of subscriptions, estimated at $4.75 Million annually, a cap of annual increases at 2%. Like the University of California agreement, there is a discount of 15% on APC charges, with the exception of 10% for The Lancet or Cell Press. While there is a discount for APC charges, unlike UC this is not applied to the subscription component.

While this is still essentially a subscription plus agreement, it offers a new type of roadmap for negotiations and structuring relationships between academic institutions and publishers to study over time, delivering on lower costs for libraries and other perks like the pilot on copyright reverting to the authors. The libraries may pay less in subscriptions while Elsevier also collects discounted APC fees for open access, mostly paid directly by funders through grants, researchers, departments, or administration. Taking the APC charges into account, spending that may have once been concentrated in the libraries materials budgets is now distributed.

Both agreements provide useful experimentation and point to the increased need for ongoing analysis, especially if Elsevier will provide Texas with annualized data on all institutional open access publishing and APC’s so the libraries would have a more complete picture of open access spending at their institutions.

New Library Roles in Open Scholarship

While these changes are exciting new developments, the institutional and library changes cut closer to the heart of a deeper transformation that goes far beyond the published article of record, including the wider scope of changes in how research is conducted, documented, disseminated. Funding these changes will continue to include increased analysis, experimentation, adjustments and growth by all players, publishers and academic institutions.

Libraries and their academic institutions have roles in also supporting published and unpublished scholarly outputs. Sami Benchekroun, Co-Founder of Morrissier, has said only 9% of research presented at conferences is published. (“The Potential of Expanding the Research Lifecycle Through Digital Transformation and Cultural Disruption,” January 19, 2023)

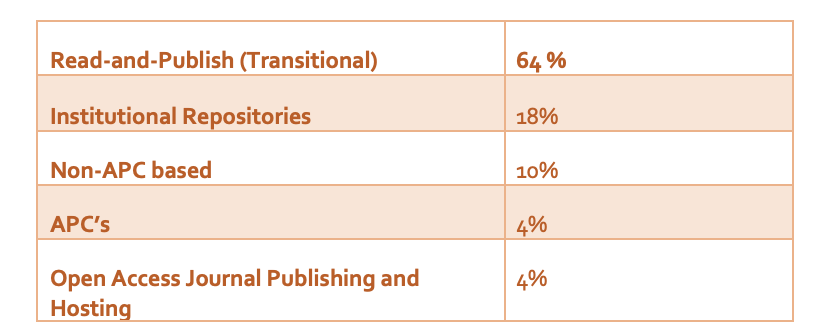

A survey by the Association of Research libraries (ARL) of open access spending is useful because the scope is much broader, reflecting the full range of library funded activities beyond agreements with publishers. The Association of Research Libraries surveyed US ARL member libraries in May-June 2022. (Hudson-Vitale & Ruttenberg, “Investments in Open: Association of Research Libraries US University Member Expenditures on Services, Collections, Staff, and Infrastructure in Support of Open Scholarship”)

It suggests the value of new ways of evaluating spending and data collection to reveal a more complete picture of library-supported spending on open scholarship and how this is changing. While ambitious, this study does not include open education resources, research data, or membership in advocacy organizations. The breakdown includes:

Note: ARL also favors using the word “transitional” to “transformational.” The first category includes “publish-and-read,” transformational, etc.

We appreciate the ambitious nature of this survey and difficulties collecting data. One would hope ARL continues to provide this survey, refining and expanding scope. For instance:

- Further breakdown of the first category would be useful.

- Since this survey focuses on library budgets, it does not reflect a key data point of APC charges paid for by other departments. It would create a more complete picture if libraries could request this data from publishers when they negotiate new agreements to form a more accurate picture of open access publishing for the entire institution.

Zooming out another layer, a 2022 NISO Roundtable on the Library Role in the Research Process highlighted new and changing roles for libraries in a digital landscape. Libraries are involved in facilitating, creating, and managing research outputs far beyond articles and books published by third parties. Within academic institutions, lines are blurring, with new roles and collaborations between libraries, IT departments, and administrative functions supporting open scholarship. As examples, there are new working relationships between IT offering high- speed computing and other resources, administration managing grants and faculty exposure, librarians helping to develop data management plans for grants, facilitating and sometimes creating research outputs like multimedia objects, data visualization, and hosting digital scholarship and library publishing. As an example, Sayeed Choudhury, Associate Dean for Digital Infrastructure, Applications, and Services and Hodson Director of the Digital Research and Curation, Carnegie Mellon, highlighted roles in supporting not just open data but open source software.

Within this context, libraries are revisiting priorities, changing staffing requirements, and changing perceptions of administration. The landscape is not static for the major players with new types of services, collaboration, skill sets, and the need to experiment, analyze and document what is working and what is not. In addition, while slow to change, we think it likely that there will be changes in how researchers and their output are evaluated. When and if that happens, systems that support their full range of outputs will be essential “a very big deal.”

Conclusion

There is change and transformation to new roles, relationships, and services supporting open scholarship. The library / publishing services of the future will look different. But definitions and context matters, especially when it affects value to the scholarly community and setting priorities for funding and budgeting.

The desire to shock the publishing industry has accelerated adoption of open access business models. Because of cOAlition S, the expression “transformative arrangements” is likely to have some persistence, even if a misnomer. One can see tacit acknowledgement of this by how often the word, “transformative” is put in quotes as if to say “the so-called transformative….” Others have switched to clarifying by calling these changes “transitional,” or “publish-and read,” etc. Otherwise, one could ask the question, “What do you think of transformative agreements?” And the response might be “What do you mean by that, how transformative is it or are these new business models working for us?”

Where it becomes more of an issue is when one aspect of the changing dynamics of open scholarship is mistaken for the whole. It assumes library materials budgets are static sources of funds for one purpose instead of part of a larger budget for services and changing demands to acquire resources, open and subscription, for their users and to fund new demands for open scholarship services.

Still, there are many new and exciting changes and a sense there is “no going back” to previous ways of creating research outputs or doing business.

- Changes in how researcher output is evaluated and rewarded.

- Agreements are likely to continue to be complex, involving experimentation and monitoring.

- More detailed analysis of resources, business models, subscriptions and services are increasingly important, including services like Delta Think Open Access Data & Analytics Tool, Unsub, etc. to inform decision making.

- Libraries could / should include requests for any APC funding at their institutions as part of new agreements to provide a more complete picture of open access spending.

- Roles and relationships between funders, publishers, administrators, IT departments and libraries and the skills required to offer services are likely to continue to evolve.

Adopting the JISC language to refer to changes in publishing to open access business models as more of a transition than a transformation seems like an easy solution to “the language problem.” Publishers and libraries are finding new ways to work together to provide resources and collaborative support for scholarship. The transformative aspects of research institutions towards open scholarship and libraries supporting new types of scholarly output, new potential rewards systems and services suggests only the beginning of changes defining the future landscape and the roles all players will have in shaping this future.