Why “what is a preprint?” is the wrong question

At ASAPbio, we’ve generally defined a preprint as an article that has yet to see the completion of journal-organized peer review. But this definition is imperfect (as we’ll discuss below) and isn’t universally shared. For example, an authoritative resource on journal preprint policies, SHERPA-RoMEO, says in its FAQ, “Publishers may use the term pre-print to define all forms of the article prior to print publication. SHERPA follows an academic practise of defining pre-prints as a draft of an academic article or other publication before it has been submitted for peer-review or other quality assurance procedure as part of the publication process.” bioRxiv’s policies resemble (but don’t exactly match) SHERPA’s first definition: it hosts scientific manuscripts prior to journal acceptance. And, adding to the mix, at the NFAIS Foresight Event on preprints, Kent Anderson used the term to refer to manuscript he’d circulated privately to colleagues, but not posted publicly. Chiarelli et al have proposed six values that factor into varied definitions of the term, summarized in figure 1.

Confusion over the term may be cause for alarm from the perspective of policymakers or meta-researchers. Without a single definition of “preprint,” uncomfortable questions abound. How can we measure the growth of preprints when we can’t even be sure which manuscripts are preprints and which are not? How can funders recognize preprints as research products when some of them are not archived or distributed openly? And what papers can a reader trust?

It’s no wonder that calls for a definition of “preprint” recurred at the NISO-NFAIS preprint event. After all, having a single definition would make it easier to assume that all articles bearing have undergone the same degree of scrutiny.

But viewing all preprints with the same eye parallels the fallacy of treating everything that has supposedly been peer reviewed as gospel truth. It’s convenient, but also wasteful and dangerous. Dangerous because heterogeneity in screening practices is inevitable, and wasteful because it ignores in-depth screening and review when it does occur.

Rather than trying to compress all the information about the “state” of a manuscript into the assumed characteristics of a simple label, we need more transparency and clarity about the screening, review, and validation operations that have been performed.

Two levels of transparency are needed. The first is at the server (and for that matter, journal) level, where better descriptions of review and screening policies are needed to help guide authors in choosing where to submit. The second level is at the individual article, which is most beneficial to readers. As Neylon et al note, variation can occur within a single publication venue; as pointed out by Carpenter, there is often no information beyond on manuscript state beyond the name of the container in which it appears.

Below, I provide some examples of the potential variation among manuscripts that are all called preprints, and the kinds of metadata that could be exposed.

Preprint servers (and journals) have different screening practices

In 2016, two Danish researchers posted a very unusual preprint and accompanying underlying data. Based on the scraped OKCupid profiles of 70,000 users, it contained, as reported by Forbes, “usernames, political leanings, drug usage, and intimate sexual details” that enabled the re-identification of (unwitting) participants.

The repository they used, OSF, did not, and does not employ pre-moderation, meaning that content goes live before human scrutiny. (Note that this does not necessarily apply to the community-run servers hosted on OSF preprints).

At the other end of the spectrum, medRxiv requires authors to include a competing interest statement, declaration of compliance with ethical guidelines, appropriate reporting checklist, and trial ID of any clinical trials.

The screening policies of many preprint servers can be found online in varying levels of detail. In order to provide a more standardized description, ASAPbio Associate Director Naomi Penfold has been collaborating with Jamie Kirkham (University of Manchester) and Fiona Murphy (independent consultant) to collect a survey of the screening and archiving policies of preprint servers. We expect the resulting directory of preprint servers to be a useful tool to help authors, funders, and institutions identify servers that comply with their own desired best practices. Stay tuned (via Twitter or our newsletter) to be informed of its release.

The problem of hidden or unclear screening policies is not unique to preprint servers. As part of a landscape study, we found that ⅓ of highly-cited journals don’t reveal whether they perform single, double, or non-blinded review. To address this issue, ASAPbio is working on Transpose, a database of journal policies on peer review and co-reviewing. Ideally, however, this information would appear on a journal’s website and systematically made available in a standard form across all journal databases and indexes.

Individual articles on the same server (and journal) have different states

Many preprint servers provide a useful disclosure near the top of the page warning potential readers that the manuscript they’re reading has not been peer reviewed. This is a helpful precaution when readers unfamiliar with the policies of the server come across papers - especially highly interesting papers that are likely to garner broad attention.

The only problem with this blanket statement is that it often isn’t true.

For example, papers on bioRxiv may be:

- Revised after being rejected after review by a highly-selective journal for reasons of novelty/impact

- Directly accompanied by journal-generated reviews (this will become more commonplace with the Hypothesis-based TRiP initiative)

- Reviewed by numerous non-journal services and platforms, like biOverlay, Peer Community In, Review Commons, PREreview, etc (some of which are linked below the abstract of reviewed preprints)

In each case, the preprint disclosures undermines the work that’s gone into producing the existing evaluation. In the midst of reviewer scarcity, we should conserve, rather than obscure, the valuable resource of review. After all, some of these preprints will have undergone more screening, checks, and peer review than is performed at some journals.

Of course, the problem of insufficient detail about review and editorial practices is not unique to bioRxiv. Beyond variations in any given review process, journals might have different policies for different types of manuscripts. For the benefit of readers, the state of the journal articles should be clear, too. A framework for concise expression of peer review attributes was proposed by the Peer Review Transparency project.

Moreover, peer review is not the only state change that matters. Whether authors have signed disclosures and whether the work has passed checks to ensure its integrity (and that of the resources enclosed or supplements or linked from it). Some progress toward reader-visibility of these already being made with implementation of OSF badges.

Outlook

In an ideal world:

- Preprint servers would qualify their now-blanket disclaimers (but also provide more detail about screening workflows)

- Journals would state their peer reviewing and screening policies clearly

- Funders and institutions would specify what qualities they want from preprints (archiving, public access, etc) and journals (eg statistical review, data checks) to help ensure that funded work will be appropriately processed

- Everywhere articles are displayed, they would be accompanied by a description of what checks have been done and by whom. Readers would be able to easily access the fingerprint of an article’s state at at various levels of detail and compare it to best practices in a given field.

Because details about an article’s state are complicated, they likely would need to be presented in a way that provides a simple overview at a glance, but offers readers the opportunity to zoom in to see more detail, annotations, and links to external material or review reports.

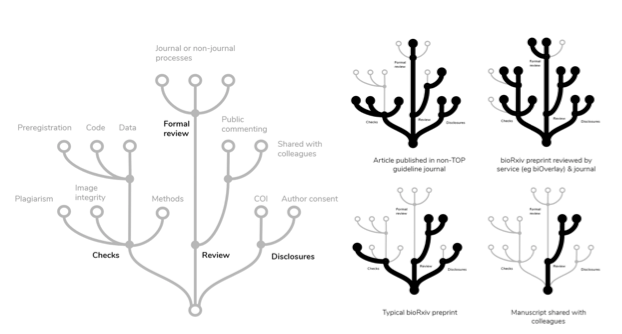

As one solution, information about an article’s state could be conveyed in tree diagrams that cluster related operations. For example, integrity checks that operate on the manuscript itself (screening for image manipulation, plagiarism, and incomplete description of methods) are related to those that look beyond the manuscript (eg ensuring the existence of code, data, or preregistration). The example tree presented above at left is certainly not complete; any practical implementation would have to enable the inclusion of TOP guidelines, Open Review badges, and further details about the nature of formal review.

The advent of preprints in new fields presents an opportunity to question what kind of screening, checks, and validation we expect and need from scholarly works. The breadth of content states on preprint servers is an object lesson: the container in which a manuscript is found does not necessarily define its state.

As Neylon et al wrote,

“We cannot discuss the difference in standing between a preprint, a journal editorial, and a research article without knowing what review or validation process each has gone through. We need a shift from “the version of record” to “the version with the record”.”

So instead of asking “what is a preprint?”, we should be asking “in what contexts and to what degree I can trust this article?” The answer lies not in the name of the container, but in the records of state changes that are largely invisible.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Naomi Penfold, SJ Klein, Sam Hindle, and Jennifer Lin for helpful comments.

Disclosure

I am employed by ASAPbio, a non-profit organization working to promote the productive use of preprints and open peer review in the life sciences. ASAPbio is partnering with EMBO to launch Review Commons, a journal-independent review service, and is working on the Transpose database. I’m also on the steering committee of PREreview, which is an advisory body.